“Just Letters” A Guest Blog About Brain Injury - by Greg Pastore

Improving my skiing and providing quality ski-lessons meant pushing my limits. I needed to ski past my ability with no concern for safety. Skiing in Vermont was the best place to achieve my goal, even though I had a series of jarring falls.

I was suddenly transported away from the mountain. I stared at a black and white clock on a blank wall, which read 10 AM. I decided to get up from bed and explore the uninspiring surroundings. Yet, I was stuck. I tried turning my head, but my neck didn’t cooperate. I wanted to turn my head with my hands, but they didn’t respond either.

I tried shouting out of fear. Where am I? Why can’t I move my body? How’d I wind up inside on a bed? These were questions flooding my panic-stricken mind. As I tried to scream, not a sound left my body. A woman in scrubs came in to tidy up my room. Soon after, a priest and my frightened parents arrived at the foot of my bed. Why were they here?

It didn’t occur to me until days later that I had been in a ski accident and was totally paralyzed. A merciful doctor diagnosed me with locked-in syndrome. A blot clot formed in my neck, broke free, and entered my brain stem causing an ischemic stroke; I was lucky to be alive. He didn’t need to explain further – I was trapped in my body or ‘locked-in.’ What hope did I have to live a normal life? I’d ruminate on this until the words lost their meaning.

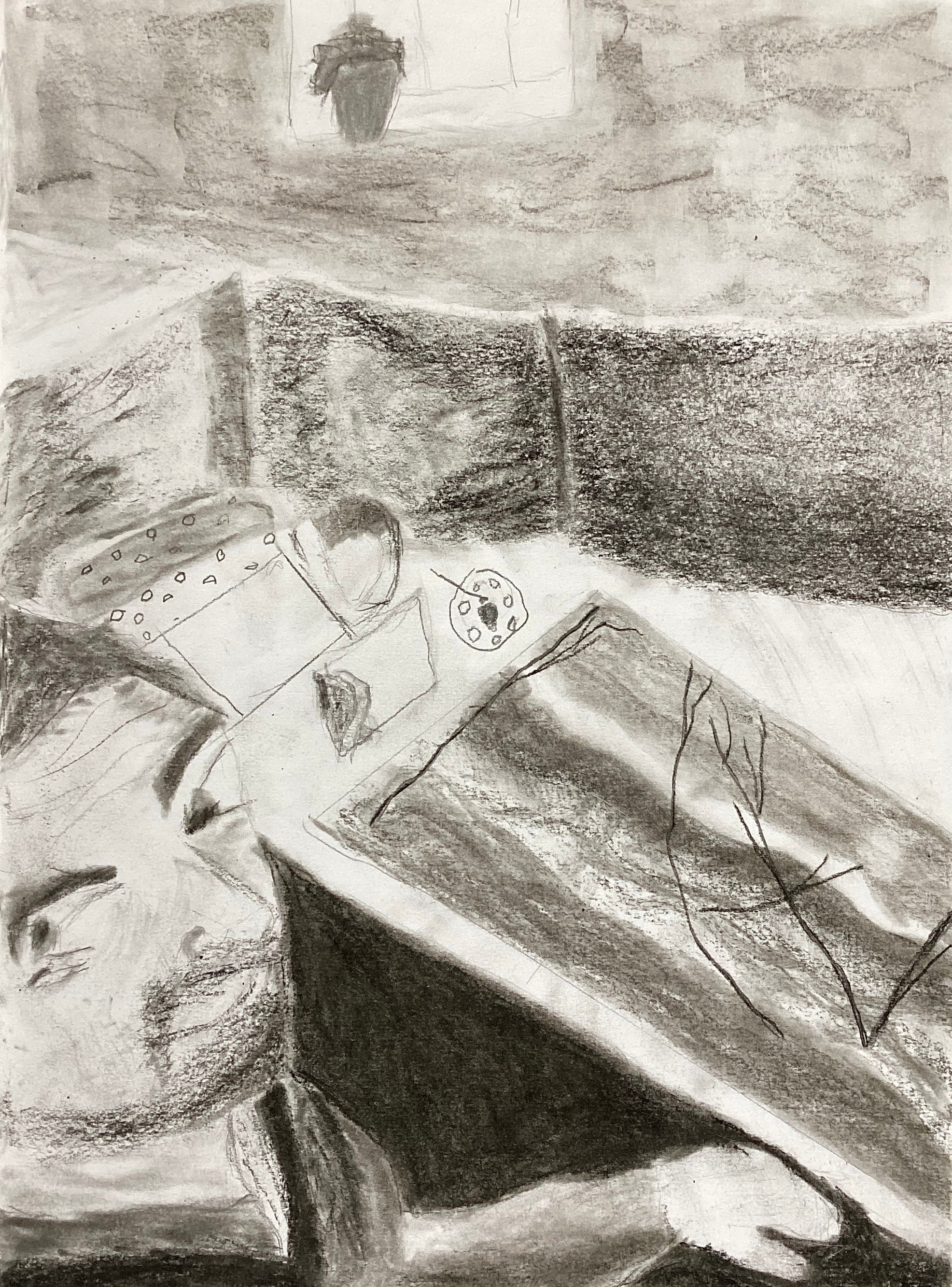

After eleven years of intensive physical and occupational therapy, I regained lost movement and ability in my eyes and left arm. This has enabled me to paint and draw. I was certain my life was over – I couldn’t imagine doing anything again. The fact that I can now paint and draw a self-portrait is amazing. I often give myself the reminder: remember, you couldn’t do anything. That I came this far – no matter the journey – breathes substance and meaning into my life. If being locked-in meant living with minimal ability, the least I could do was listen to medical professionals and hope for a way out. This is true because the contrast between then and now is clear.

Despite my newfound abilities, drawing a self-portrait seemed a daunting task. I was never a good artist, so any drawing of my face would be laughable (additionally, I didn’t like the idea of staring at myself all day). But I focused and it came out better than I thought. It gave me a sense of accomplishment and confidence. Confidence because I can do anything if I give a task full attention.